How to Build Wing Ribs out of Old Orange Crates

A fellow who has been following my posts about building airplanes on the cheap wrote to say he'd found plenty of straight grained hemlock 2x4's at his local Home Depot. Then he said he couldn't use it because it was full of knots. I smiled at that, fired off a message telling him not to worry about the knots. The knots would vanish as the work progressed. That got me a rather grumpy reply about wasting his time.

Apparently the fellow doesn't believe in magic :-)

Magic has been defined as anything we don't understand. At one time the ability to do long division or work with fractions was considered magical. Making knots vanish is no more difficult than long division.

STICK RIBS

Have you ever made one? Probably not <maybe you have, if you’ve been to the EAA convention, they’ve been teaching kids to build ribs for years – RRY>. Which is kinda sad because stick ribs are a key factor in a building a strong, lightweight, efficient and INEXPENSIVE wing. Once you know how to build a good wing the rest of the airframe is relatively easy.

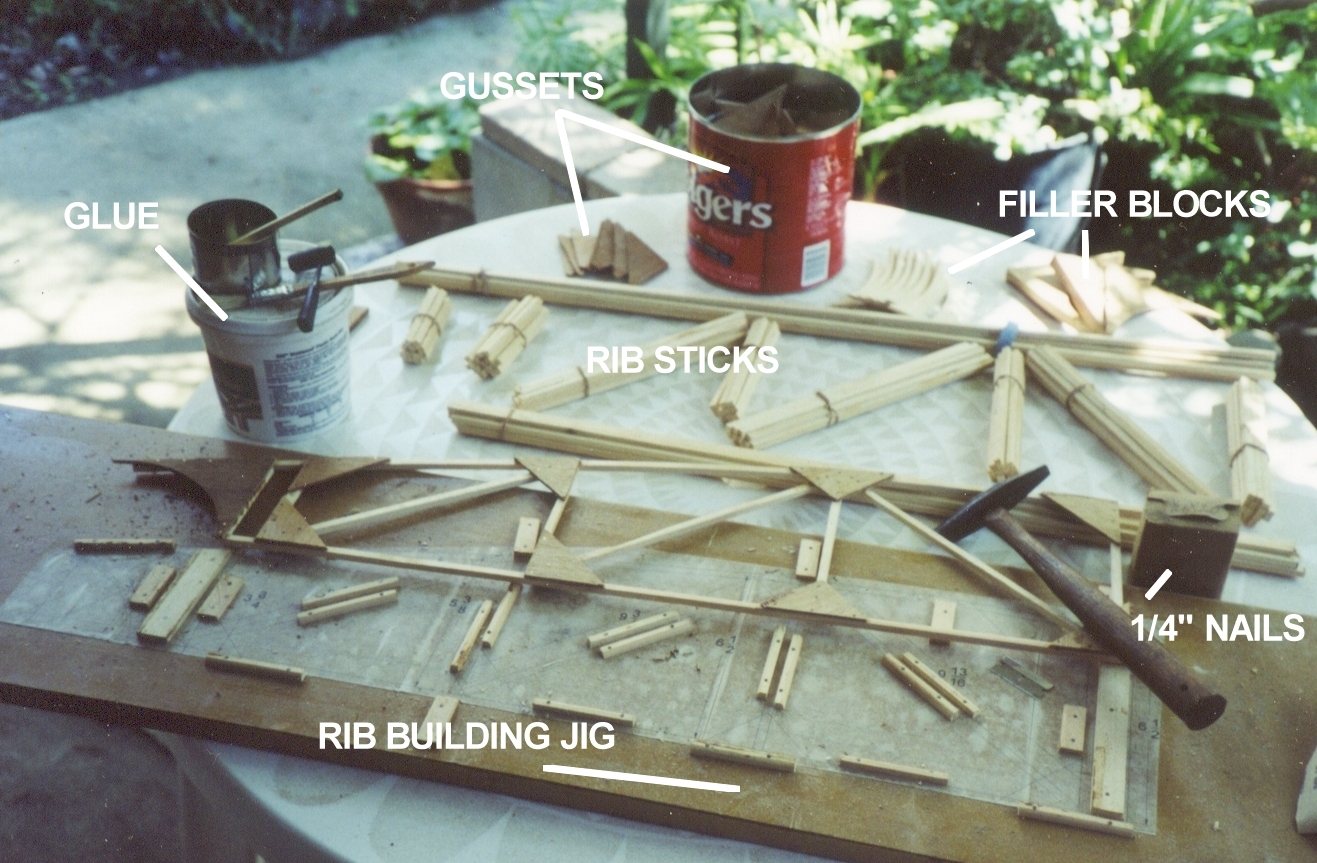

To give you some idea as to what I'm talking about I've provided a couple of photos of stick rib construction and a drawing of the airfoil. Mr. Ryan Young, the Coast Guard's answer to Samuel Pepys, has allowed me to pin the illustrations on his electronic wall <For which I’m repaid in such outrageously complimentary and undeserved comparisons, by someone who has actually read the Diaries. – RRY>.

Making ribs is a fundamental Rite of Passage for homebuilders, each of whom has their preferred method. Some argue for fitting each individual stick, others for leaving them square; some insist on clamps versus fasteners, other feel the only practical fastener is a Monel staple; some use circular gussets, others are polyform but most use some version of a triangle. And then comes the Glue Wars...

Oddly enough, the myriad differences in rib construction vanish along with the knots as soon as you get some daylight under the wheels. All of that tiresome but socially-required Homebuilder Bullshit boils down to the basic questions of strength, weight, cost and convenience. Build your ribs in whatever way best matches your situation. So long as they are light enough and strong enough, the airplane will fly just fine. (As a basis for comparison the rib shown in the photos takes about fifteen minutes to assemble using 1/4" aircraft nails, weighs about 3.5 ounces and costs about fifty cents each, all tolled.)

STICK RIB STOCK

The longest pieces of wood in a stick rib are the cap strips - the top and bottom pieces. For a big, old-fashioned airfoil the cap strips are liable to be five feet long. The other sticks in the rib, the verticals and diagonals, are shorter; maybe a foot long, max, with the others being even shorter than that. On a modern airfoil, say a 4415 having a chord of 48" and built with a D-cell leading edge, the cap strips are about three feet long and the longest diagonal is maybe nine inches, something like that.

The above is worth mentioning because it will help you understand why the knots drop out of the equation.

To turn a two-by-four into rib stock you set up the saw for whatever thickness you want then rip the two-by into laths. Ignore the knots, just cut right through them. If the lath breaks at a knot, don't worry about it. Once all the two-by-fours have been ripped into laths, run them back through the saw to produce rib stock. If you want square stock you don't even have to reset the saw.

When using locally available lumber the wiser course is to give yourself plenty of extra wood to work with. I generally cut about twice as much as needed, selecting the very best of the bunch for ribs.

When ripping the laths into rib stock you will again cut right through the knots. And again, some of the pieces will break at that point. No big deal.

After you've reduced your two-by-fours to rib stock you'll have a huge pile of sticks. Some will be full length, others will be shorter, having broken at a knot. Don't worry about it. We'll use the long pieces for our long sticks, short pieces for short sticks, discarding any knots we encounter along the way.

Now comes the grading. You're looking for clear, knot-free pieces having flat grain with a run-out of at least one-in-fifteen and long enough to serve as cap strips. Put the pieces on your work bench and examine the grain. Looking down at the piece, the grain should be looking up at you. If you can't see it, roll the piece over to expose the other edge. If the grain is not clearly visible on one edge or the other, discard the piece.

It isn't uncommon to find grain of sixteen to twenty in a two-by-four of Western Hemlock. The more gain, the higher the density and the heavier the piece, so don't go overboard here. I'm happy with two to four annual rings across a quarter-inch rib stick.

Although grain run-out is a critical factor in the strength of the wood, any run-out greater than the length of that particular piece is acceptable. For example, on a diagonal that is nine and a half inches long you should be able to follow the grain for the length of the piece. That means almost any stick will meet the specs for the shorter members in a rib. The reason why this is so has to do with the manner in which wood carries a load and may be confirmed by a few simple experiments.

Once you've selected the pick of the litter for your cap strips, you're home free; the rest of the job is a no-brainer. Cut your cap strips to length and bundle them using rubber bands. Use the residue to make up the vertical and diagonal pieces.

WORKING WITH WOOD

I haven't bothered to mention the need for finger-boards (some call them ‘feather-boards'), pusher-sticks, hold-downs and a zero-clearance shoe. I consider this sort of thing to come under basic woodworking skills and have assumed anyone building a wooden wing or fuselage would be familiar with them. <another helpful accessory for ripping thin stop is a strip ripping gauge – RRY>

Fabricating ribs, stringers, longerons and spar caps from locally available materials assumes the as-sawn rib stock will have a reasonably smooth surface and be of the required size. If you don't have a good saw or if you aren't a good sawyer, it might be wise to enlist the aid of someone with better equipment or more experience.

Some folks, mostly those who have never built anything, will argue that all of the wood in an airplane should be milled to size and free of splices. Wood that has been planed smooth certainly presents a more attractive appearance and I strongly recommend it for furniture. But as-sawn stock works perfectly well for ribs. In fact, if you order rib stock from a spruce supplier it will arrive in planks of the required thickness (i.e., one-quarter, five-sixteenths, etc), which you are then expected to rip to the required width.

Of course, if you're a skilled woodworker with a shop full of tools that includes a surface planer (NOT a joiner), and if you can afford the additional wastage, then you would probably mill all the stock you need to the required size. But many simply cannot afford neither the tools nor the wastage. Accurately sawn, with an eighth-inch kerf, about 60% of the material will end up on the floor as sawdust. Even allowing for the smallest possible clean-up cut in the surface planer will raise the wastage to about 75%

As for splicing, a scarf of twelve-to-one will typically equal the strength of the parent material and is often stronger. Just as we must splice short pieces of plywood in order to make long ones, when using locally available materials for our spars, caps and longerons, splicing is usually required not only to make up the required length, but to eliminate any knots. All of the handbooks on the maintenance of wooden aircraft components contain examples of proper splicing procedures.

R.S. Hoover

Here’s the stuff you need to build ribs:

And here is the stuff, assembled in the jig: